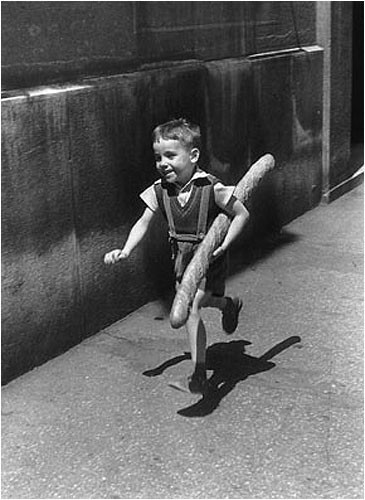

Robert Doisneau.

Chasseur d’images.

What the eye had not yet caught, but that captures the image.

“I feel euphoric to observe… until I can no longer.”[1]

“You arrive at a place, I like, there is something… there is a crucial moment when everything is in harmony, among all around… Then people come into the photo and click, it’s done!

It’s very stressful, when I snap the picture, because : will I lose it ? …no, it turned out well!”

Moved away at a very young age from his family and the suburbs which “…I hated to the point of wanting to destroy it…” Doisneau remembers, at twenty-two he meets Pierret and they decide to get married right away : Robert works taking his wife with him, and soon their two children, Annette e Francine as well as brothers-in-law, friends like a lively tribe from which he will never part.

Those are the years, between 1934 and 1938, of his job as a workman in ‘Renault’.

“Renault has not at all sense of humour – Robert comments about his employer – and is able to govern only striking terror into others…” But Monsieur Renault doesn’t like the photo reportages in his factory and, above all, the criticism of the ‘system’, the frequent absences to run to the photo lab to develop films, and so the dismissal comes. However Doisneau begins to take ‘photography’ seriously and from those occasional photo reportages he sold to newspapers, he is able now to get more permanent jobs.

It is already the time of Nazi propaganda, and then of what Doisneau calls “the fucking war…” He works together with a partner, Paul Baravet said Babà who goes touring Paris by bike to bring photos to clients and who, with his innocent air, is able to save many of them from deportation and from concentration camps. Robert always refused to photograph what cannot be said, also in his most toughest photos the light aspect of life prevails.

There is “…a lot of poverty everywhere and bitter life in Paris, but you can think that people know how to have fun”, he also comments coming back to photograph the suburbs, and he looks carefully at new dimensions, colours.

“In order to apologize, they coloured…”, he says never being caustic.

The eye doesn’t catch immediately what makes the ‘image capture’ : it is only later, when developing a film in one’s laboratory, that ‘one’ detail collected by the before recording it, finally becomes clear. And Robert realizes that only after comparing the result with what he didn’t remember to have seen.

Some time later, when ‘Humanist photography’[2] – which is already a concept of life and of everyday life - will born, Doisneau will name for the first time ‘the optical unconscious’ which can orientate towards the ‘catching’ by the eye that captures the image, and that is secondary as a matter of fact to the skin contact.

“People in the States dance keeping at a certain distance…”, Robert observes quite amused during his stay there in the ‘80s, when he already works for ‘Life’ magazine.

Those are the years when, right in the States, the photography market was born : Doisneau presents his own ‘portfolio’, curated by Monah Gettner, an actress featured in the documentary-film “Robert Doisneau, le rèvolte du merveilleux”.

Doisneau’ work will be unexpectedly collected by the greatest U.S.A. photographers who will also become excellent interpreters of the new Art.

“You snap a photo – Robert Doisneau said – and it’s already in the past.”

Marina Bilotta Membretti / Cernusco sul Naviglio - November 29, 2019

[1] The quote, as the following ones in this article is taken from “Le rèvolte du merveilleux” (2016), documentary-film by Clementine Deroudille and, beyond Clementine Deroudille, with Eric Caravaca, Sabine Azèma, Quentin Bajac, Jean Claude Carriere.

[2] The ‘Humanist photography’ was born in ‘30s with Henry Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) : “the subject is ‘man’, man and his short, fragile, threatened life…” It becomes then a social and public phenomenon in 1950, just finished the 2° World War with “Le Baiser de l’Hotel de Ville” by Robert Doisneau, published withou noise on the U.S.A. weekly “Life”, to which Doisneau already collaborates : this photograph indeed will become the Manifesto of a new trend. Doisneau will gain fame among the general public with the Exhibition created in New York in 1955, “The Family of Man” at care of Edward Steichen.