Help!

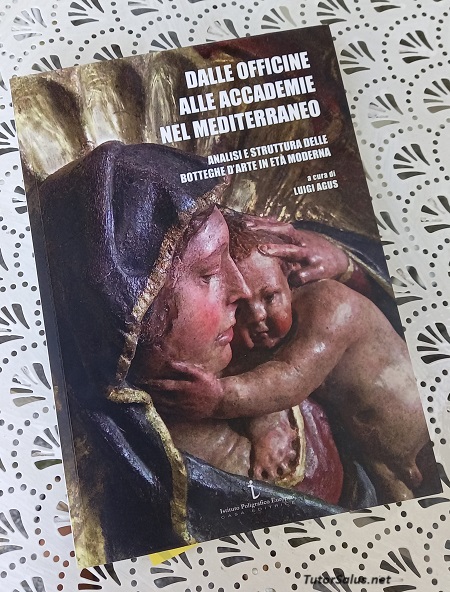

In the picture, a detail of the ‘Madonna con Bambino’, Donatello and Michelozzo’s school (1430-1431), golden and polycrome terracotta - Bonacardo, Santuario di Bonacatu. Drawn from the cover of the essay ‘Dalle Officine alle Accademie nel Mediterraneo. Analisi e struttura delle Botteghe d’Arte in età moderna’, at care of Luigi Agus (2023) Istituto Poligrafico Europeo Casa editrice.

Artist or artisan ?

Here’s the legitimate question Luigi Agus[1] must have asked himself in undertaking his recent essay where he reproposes a few study seminars presented in 2017 at the Academy of Fine Arts ‘Mario Sironi’ of Sassari (Italy) and other works from an ongoing project at the Department of ‘Comunicazione e Didattica dell’Arte’ at the Academy of Fine Arts in Palermo, intended to involve also a non-specialistic audience for “a greater depth of the issue”.[2]

Which is the origin of the Italian Academies of Fine Arts ? They arose in our peninsula around 1500 to lift the figure of the Artist from the Master of the Art workshop, who was losing independence and then the specificity of his work due to the economic weakening of the Corporations, in favour of clients with assets and ambitious for social recognition. Chiefs of government or rich bourgeois, the patrons encourage and subsidize the birth of the first Art Academies, as a voluntaristic act of independence of the Art from the daily work.[3]

However every Artist would absolutely continue to need, both technical expertise in implementation and the presence of workers who had to be entrusted with a large part of specialist work. This was true for frescoes and paintings, for statues and sculptures, for civil and religious buildings : so where was the distinction between Artist and artisan that Art instead wants undividedly, or at least decidedly collaborative ?

To the point of asking : can an artisan become an Artist ?

It is the case of this ‘Madonna con Bambino’ at Bonacardo, in the municipality of Oristano, a rarest example of Renaissance in Sardinia, restored less than ten years ago for the certain attribution by the Superintendency of ‘Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape’ that then followed the work started in 2015 and ended in 2016.

The hypotheses on the commission – which seem to point the good relationships between Tuscany in 1400s and the ‘Giudicato of Arborea’ – don’t get however to identify the artisan-Artist who made it.

“The model is definitely Donatello, but the iconography still distances itself from the creations of the great sculptor for the reason of the accentuated knot of the two figures, their becoming one. The detail of the hand of the Madonna on the Child’s head and the close contact between cheek and face of Mother and Son are motifs clearly dependent on a Donatellian prototype, whose most immediate reference seems to be the ‘Madonna di Verona’[4]. As a matter of facts, there are numerous stucco, terracotta and papier-mâché versions of this work, none of which is an original, as if Donatello had only created a model specifically intended to be reproduced.”[5] The autonomy of Art can only rely on Workshops that Art doesn’t disdain indeed, and in which the models, the techniques, the tools come from pre-existing Artists-artisans and their experiences.

And “where there was no Corporation that regulated its formation“, to become wood sculptors for example, “also in this workshop, reference is made to lying wood, to study models which could be paintings or drawings and to the tools of the trade” [6], as can be seen today from reading the Archives.

Technique “as virtuosity, as an exceptional skill, as an experience of solitude of the creative genius”[7] and technique “as a sharing experience, as a component of a didactic project which unites the different components of knowledge present inside and outside the Academies… This will once again give a role to the Academies of Fine Arts, which perhaps we should rename Academies of Good Techniques.”

Thinking is not born divided, as a matter of facts, mainly thinking retains a non-manipulable memory and from which continually draws also when ‘thoughtless’: but there is ignorance about this , and ancient naivety, even fossil. As if thinking doesn’t know how to ask for help.

Marina Bilotta Membretti / Cernusco sul Naviglio – October 25, 2023

[1] Luigi Agus is a PhD and art historian, now he is teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts of Palermo, after having held the same position at the Academy of Fine Arts of Sassari (Sardinia). Corresponding academician of the Real Academia of Cordoba (Spain), accredited researcher at the national archives and at the National Library of Spain, he has several publications to his credit.

[2] ‘Dalle Officine alle Accademie nel Mediterraneo. Analisi e struttura delle Botteghe d’Arte in età moderna’, at care of Luigi Agus (2023) Istituto Poligrafico Europeo Casa editrice, ‘Introduction’ pg.9

[3] The Academy of Drawing, the first Art Academy in Italy, was established in 1563 in Florence by Cosimo I dei Medici and with theoretical support of Giorgio Vasari.

[4] ‘Madonna di Verona. Madonna con Bambino’, Relief (1447 – 1453), Workshop of Donato Bardi said Donatello 1386 – 1466). Now it is at the ‘Museo Nazionale del Bargello’, in Florence (drawn from the General Catalog of Cultural Heritage).

[5] ‘Un raffinato esempio di Bottega rinascimentale in Sardegna: la formella in ceramica policroma della Madonna di Bonacatu (primi decenni del XV secolo)’, by Patricia Olivo – pgg. 92-93 in ‘Dalle Officine alle Accademie nel Mediterraneo. Analisi e struttura delle Botteghe d’Arte in età moderna’, at care of Luigi Agus (2023) Istituto Poligrafico Europeo Casa editrice. Patricia Olivo, graduated in Italian Literature at the University of Cagliari and specialized in History of medioeval and modern Art at the University of Bologna, is art historian director of the Ministry of Culture : she carried out protection and research activities in Florence, and curator of various enhancement projects in collaboration with the municipalities of Cagliari, Oristano and with the Departments of Art history and DICAAR of the University of Cagliari.

[6] ‘Note sui modelli di formazione artistica e socioeconomica tra Sei e Settecento. Le Botteghe degli scultori in legno : i contratti di apprendistato’, by Isabella Di Liddo – pg.175 in ‘Dalle Officine alle Accademie nel Mediterraneo. Analisi e struttura delle Botteghe d’Arte in età moderna’, at care of Luigi Agus (2023) Istituto Poligrafico Europeo Casa editrice. Isabella Di Liddo is associated professor of History of modern Art at the University of Bari, she carried out research at Italian and foreign Universities (Santiago de Compostela, Murcia-Spagna, Historical Archive of Banco di Napoli. Specialist in wooden sculpture and South Italy architecture, she has several monographs to her credit, among which some already presented at Study Conferences. She cared the essay ‘Santi Patroni in Puglia e in Italia meridionale in età moderna’ (2017).

[7] ‘Morte e rinascita delle tecniche nel futuro delle Accademie’, by Claudio Gamba – pgg.205-206 in ‘Dalle Officine alle Accademie nel Mediterraneo. Analisi e struttura delle Botteghe d’Arte in età moderna’, at care of Luigi Agus (2023) Istituto Poligrafico Europeo Casa editrice. Claudio Gamba, PhD in History of Art, published a number of essays on the critical work of foreign and Italian art historians. He cared for ‘Skira editor’ the volumes on Michelangelo, on the ‘Musei Capitolini’, and on the ‘Vatican Museums’. He worked for the ‘Sottosegretariato of MIBAC’ (2007-2008) and for ‘ISCR’ (2008-2009). Now he is teacher at the ‘Brera Academy’ of Milan, after teaching at the Academies of Fine Arts of Frosinone and Sassari.